Photographer Edward Curtis wrote of his 1927 visit to Hooper Bay:

“Slimy clay prevails everywhere. In summer shelters and winter houses alike, it oozes through the sleeping matting and clothing, kaiaks, and everything in use becomes coated with it.”

To better understand my own artistic context when I moved here, I began to ask around about historic ceramics in the far north and was surprised when I was told, repeatedly, that there was not much of a ceramics tradition. I began to search for evidence of one, compiling photos of pottery sherds from archaeological collections and anecdotes of pottery making from historic accounts and early ethnographic interviews. I soon realized there had been a widespread and long-lasting tradition of ceramics in Alaska. Ceramic technology was introduced thousands of years ago with cultural migrations across the Bering Straight and continued in many communities until the introduction of metal wares after European contact. The contemporary lack of awareness of this tradition is a result of the nature of the wares. Due to social and environmental conditions (short and wet pottery-making seasons, limited timber, seasonally nomadic communities, etc.), arctic pottery was only fired to very low temperatures, causing it to disintegrate quickly and thus rarely appear in archaeological assemblages. In fact, the wares were fired to such a low temperature that they were still permeable to water, and most arctic pottery techniques involved the inclusion of blood or fats in the clay body, or as a finish sealant, to make them useful for cooking and storage. The following paper, written in 2012, is a summary of what I found.

Ceramic Technology of Arctic Alaska:

An Experimental and Adaptive Craft

Perrin Teal Sullivan

Introduction

Ceramic production began in the arctic thousands of years ago, and traditional methods remained in widespread use among Alaskan Native populations until the end of the 19th century. The existence of a ceramic tradition in the arctic is a surprise to many, as it contradicts common assumptions about the environment and lifestyle in which pottery making is viable and practical. A suitable climate for collecting clay and drying wares, ample fuel for firing, and an agrarian, or at least sedentary, lifestyle are generally correlated with pottery-making cultures. The hunter-gatherers of the arctic had none of these advantageous conditions and yet were capable of manufacturing functional ware to meet their needs in spite of the challenges posed by their environment and lifestyle. The widespread and consistent production of arctic pottery for thousands of years is testament to the inventive adaptations of the regional ceramic technology. The longevity of the tradition suggests that the most recent practitioners inherited techniques and methods honed and refined by the experiences of generations before them, including an intimate knowledge of raw materials and their sources. The ultimate abandonment of traditional Alaskan pottery production in the late 1880s, due to a preference for newly available metal goods, meant that ample first-hand knowledge of the processes and techniques employed for millennia still existed among elders when the first wave of ethnographers, anthropologists, and archaeologists began to document what was then referred to as “Eskimo” culture. These first-hand accounts provide an invaluable glimpse into the technology, and its myriad local variations, that allowed for a pottery tradition to flourish in the arctic. Traditional ceramic techniques and methods, as described by Alaskan Native elders to early arctic researchers, when considered along side archaeological evidence and contemporary material studies, illustrate the ingenuity and experimental nature of local adaptations to the climate and resources of the arctic and the needs of the people who lived there.

The Beginning of Pottery in Alaska

There are many different theories of when and how humans first discovered that fire transformed raw clay into a durable material, but there is widespread agreement that the manufacture of ceramics is one of the great technological advancements in the history of humanity.[1] Plastic and moldable when wet, durable and even impermeable when exposed to sufficient heat, uniquely insulating and abundantly available across the surface of the earth, clay is a material deeply entwined with human history. It is no surprise that clay plays a central role in the creation myths of diverse cultures across the globe, as the prima materia from which the creator molds the world.[2] Humans in turn have been molding clay for many thousands of years. The oldest definitively dated fired ceramics are the figurines at Dolni Vestonice, made 26,000 years ago. More recently, pottery sherds discovered at Xianrendong Cave in China were determined to be 20,000 years old.[3] Pottery was introduced to Alaska from Siberia between 3000-3500 years ago, where it was widely used along the coast of the Bering Sea.[4] During this period, western coastal areas of Alaska experienced longer periods of settlement, and the introduction of pottery and sea-mammal hunting tools indicates cultural interaction across the Bering Straight. [5] Ceramic technology was readily adopted in Alaska and spread as far south as Kodiak Island within the next two millenia.[6] In a cultural shift referred to as the Ipiutak culture, beginning approximately 2000 years ago, there was a hiatus from pottery making in northwestern Alaska, for reasons that are unclear.[7] Ceramic technology was revived approximately 1000 years ago by the emergence of a maritime-proficient culture called the Thule, which came to dominate the western arctic, spreading across northern Canada to Greenland. The Thule is considered the antecedent of the current Yup’ik, Iñupiat and Inuit cultures.[8]

The End of Pottery in Alaska

It is important to point out that thousands of years of traditional pottery production in Alaska was abandoned just a little over a century ago. The decline of production essentially coincided with the availability of cast iron and sheet metal goods acquired in trade after the time of contact.[9] Research in the Kotzebue area points to the cessation of pottery production between 1870 and the 1880s, when metal pots became widely available.[10] The durability and efficiency of the metal pots are likely the primary reason for their adoption, but an additional reason for the quick abandonment of ceramic production has been proposed: the change in domestic duties of women to meet the demands of the colonial market (fur), or perhaps an up-tick in time required to process an increased harvest of resources like seal, made possible by the use of new technologies such as firearms. This shift in economy might have meant that there were simply too many other demands on women’s time and pottery production was no longer viewed as a priority.[11]

Metal pots were not the only newly adopted containers. At the Crow Village site on the Kuskokwim River, occupied by Alaskan Natives entirely during the period of contact and subsequently abandoned, there appeared to be an adoption of European ceramics: stoneware, transfer-ware, and hand-decorated china. Wendell Oswalt, an anthropologist who worked on the site, reflected on the strange archaeological assemblage and wrote, “the tradition of pottery making is seen in its last stage at the site. The fragments of imported pottery outnumber those of the locally made ware.”[12] He also noted that although traditional pottery was scarce, many pieces of ceramic lamps were found, indicating that no better technology had been introduced as a substitute.[13] The longevity of lamp production is also apparent in a 2003 interview conducted by anthropologist Ann Fienup-Riordan with Frank Andrews of Kwigillingok on Kuskokwim Bay. Born in 1917, Andrews clearly recalled the production of lamps in his lifetime and was still able to describe the process in detail.[14] During the 1908 Vilhjálmur Stefánsson arctic expedition for the American Museum of Natural History, one of the native members of the party, Ilavirnik, put forth a compelling reason why pottery may have persisted in some areas even after metal cook ware became available: a taboo on the use of metal during fishing season. Stefánsson records that “when Ilav[irnik] was young metal pots were readily obtainable; the reason for making pottery was the prohibition against metal kettles when hooking for fish was going on.”[15] Ilavirnik came from Kotzebue Sound, but believed and stated that the taboo would have been true in other places as well, giving another possible reason for the density of lamp sherds in Crow Village.

First-Hand Accounts of Ceramic Production

That fact that pottery manufacture was only recently abandoned at the close of the 19th century meant that many archaeologists and ethnographers (de Laguna, Campbell, Lucier, Oswalt, Spencer, Stefansson, etc.) working in the arctic in the 20th century were able to find living informants who recalled the traditional processes and could give first-hand accounts of production techniques, sources of raw materials, and methods of use. The pottery making process, from the collection of raw materials to the molding, firing, and ultimate use of the ware, is divided into separate sections below so that we may highlight the similarities and differences at each step. An introduction to a few of the more descriptive informants will help identify their comments later on.

In 1951 at Elephant Point, where the Buckland River drains into Kotzebue Sound, anthropologist Charles Lucier recorded an account of pottery production from a village elder named Andrew Sunno. Sunno was born between 1857 and 1859 and described in great detail his childhood recollections of women potters and the techniques they used.[16] Archaeologist Wendell Oswalt’s excavations of the Hooper Bay Village site in 1950 allowed him the opportunity to record an account of the traditional pottery techniques from Alec Smart, an elder in his seventies and the “oldest person in the village,” although Oswalt notes many of the other elderly inhabitants also remembered the days of pottery production in the area. “Potterymaking”, according to Mr. Smart, “was the work of only the old women.”[17]

Another account of traditional pottery production was detailed by Simon Paneak, one the last members of the distinct Nunamiut culture of the northern Brooks Range, driven nearly to extinction by disease, and diaspora of the survivors, in the early 1900s.[18] Paneak was born in 1900 and emmigrated to the coast in the 1920s, only to return to the traditional encampments a decade later with a group of other Nunamiut expatriates. The remoteness of their location and infrequency of contact with the outside world meant that traditional ways of life were reestablished by necessity.[19] John Martin Campbell, a graduate student in anthropology, encountered Paneak during a 1956 fieldwork expedition, and in 1968 Paneak began a graphic annotated history of the Nunamiut at Campbell’s request. Plate 40 depicts household tools, including a flat-bottomed clay pot translated as “Pattigak” with instructions for making it written below (Fig.1).[20]

Figure 1. Clay Pot- Pattigak by Simon Paneak 1968

Figure 1. Clay Pot- Pattigak by Simon Paneak 1968

These and other first-hand accounts of pottery production depict an astonishingly wide array of techniques and materials in use at the end of the pottery-making tradition in Alaska. While this may seem to indicate a haphazard or unrefined technology, the opposite is true. Paul John, of Toksook Bay, was invited in 1997 to attend the opening of an exhibit of Yup’ik artifacts at the National Museum of the American Indian. Upon seeing the collection of artifacts made by his ancestors, he remarked, “These tools are the legacy of their ingenuity, and one can see their intelligence through their things.” [21] If the people of the arctic are renowned for their inventiveness, their ceramic technology is no exception. The variety of techniques and materials reportedly used across Alaska indicates a serious understanding of the craft, and the ability to adapt production to extremely local circumstances and resources.

Traditional Clay Sources

Clay was generally collected at the nearest convenient location, although certain spots were understood to provide superior materials. In some cases, people traveled significant distances to collect their preferred clay, and in other cases places were named in honor of the resource sought there. Andrew Sunno, Charles Lucier’s informant in the Buckland River region, reported that a slick clay was collected on the east side of the river, where a creek flowed into a straight stretch. The place was called Qiichu, which meant “clay for pots.”[22] In Hooper Bay Village, Alec Smart recounted to Oswalt that some clay was collected on north side of Askinuk Mountains, but most of it came from Nelson Island.[23] A potter would have had to plan a specific journey to obtain clay at these locations, even though clay was reportedly abundant underfoot right in the village. Photographer Edward S. Curtis wrote of his 1927 experience in Hooper Bay, “slimy clay prevails everywhere. In summer shelters and winter houses alike, it oozes through the sleeping matting, and clothing, kaiaks, and everything in use becomes coated with it.”[24] The Hooper Bay potters must have clearly understood the superior characteristics of the more distant clays, making a journey to their source worth a trip.

Frederica De Laguna, an anthropologist known for extensive fieldwork with Alaskan Natives in the 1930s, searched for many reported clay sources. One, she was told, was renowned throughout the region. She wrote, “On the west bank of the Yukon, just below the mouth of the Koyukuk…there is supposed to be a deposit of clay, which women used for pottery. Indians from many miles away used to gather here to dig out clay, camping on the shore of Yukon Island, opposite.”[25] That women traveled great distances to collect this clay indicates an intimate understanding of the pottery craft. These women knew the qualities and properties of the raw materials available to them, and made conscious choices to obtain their preferred material, even if its collection was an inconvenience. Alternatively, this specific deposit could have been the nearest source of clay for some of these potters, or the pilgrimage could have been made for the social gathering aspect. Perhaps it was a place where women could trade tips and techniques they had discovered or refined. In Barrow, anthropologist Robert Spencer observed a similar situation. In his 1959 report he wrote: “Any woman who had the skill was free to make pottery. A necessary element was a special clay obtainable at the site of kiku, a location some miles down the coast from modern Barrow at the location of Skull Cliff. Women might take a day or two in summer to go down to the site and gather enough clay. At times, the pottery was made at the place where the clay was obtained and the pots left until they could be called for by boat. Some women made a practice of bringing back bags of clay from kiku and trading some of it to other women. Only this reddish clay was adequate for pottery. A living informant recalls that one woman tried to make a pot using the local gray clay but that she was unable to get it to congeal.”[26] The evidence of continued experimentation with a variety of clay sources is indicative of the open-minded approach taken by the potters, an approach that was likely crucial in perpetuating ceramic production in a challenging and ill-suited environment.

Villagers at Ghost Creek, near Holy Cross, told de Laguna of a source at Hall’s Rapids, where yellow, brown, or white clay could be obtained,[27] and at Koyukuk Station a source of white clay was reported near Galena.[28] At St. Michael on Norton Sound, Edward Nelson reported in 1899 that pottery was widely made in the region, and that the clay he had observed in use was a “tough, blue clay” which was moistened and kneaded to plasticity.[29] He does not specify where the clay was collected.

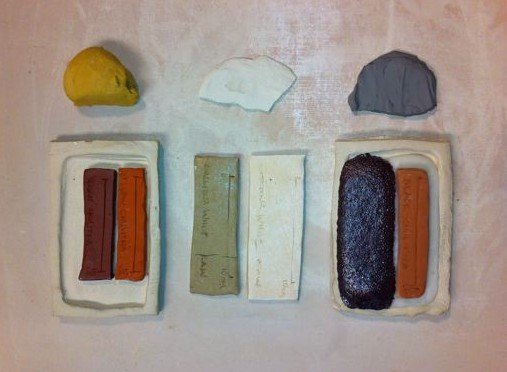

The reported range of colors and textures of the raw clay used for ceramic ware is interesting, and further indicates that potters were experimental with their sources. Rather than relying on a specific resource, they recognized a variety of acceptable clays and may have adjusted their tempers and construction style to work with the available clay. Or, perhaps they understood that clays of seemingly very different properties would have a fairly similar end result. While clay may superficially seem to range widely in composition, in most cases the variation in color comes from iron impurities and carbonaceous matter. The former would fire to a red, buff, or brown color, while the latter would burn off in the firing process. The majority of traditional pottery worldwide was made with clay called “earthenware”, which is a secondary clay, meaning it has been transported from its original source by wind, water, and other natural forces. In the process it picks up impurities, the most common of which is iron oxide. Iron acts as a strong flux for the silica and alumina in the clay, allowing earthenware to be adequately fired at a relatively low temperature. [30] This range in clay color is demonstrated in Figure 2: the raw clay is at the top of the image and below each sample is the same clay fired to two different temperatures (pyrometric cone 6 on the left, cone 04 on the right).

Figure 2. Raw Alaskan clays, fired to cone 04 and cone 6.

Figure 2. Raw Alaskan clays, fired to cone 04 and cone 6.

The samples in Figure 1, from left to right, were collected in 2011 by potter Jed Williams of Fairbanks at unspecified locations on the Chulitna River, Lake Minchumina, and another location along the Chulitna at a different clay deposit. Jed stated that he noticed the clay-rich banks while visiting these locations, and although he had no prior intent to collect clays decided to take some home to test. All were fired in electric oxidation kilns at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Ceramics department to pyrometric cone 04, and pyrometric cone 6, roughly the equivalent of 1945ºF and 2232ºF, much hotter than the temperature obtainable in an open pit fire. The dark grey clay on the far right indicates a higher iron impurity and more organic matter than the yellow clay on the left, as it is melted completely when fired to cone 6 and the grey color burned off to reveal red earthenware. The minimal processing (screening of large debris) that was required to turn these clay samples into viable pottery clay is indicative of the ease with which materials can be sourced by someone with practical knowledge of pottery. It is also likely that potters open to experimentation would be able to adjust the tempers added to the raw clay in order to correct for the qualities they desired. The creative adaptability of the arctic potter is further indicated in the variety of reported combinations of tempers, many of which are sensibly based on readily acquired local resources. In fact, Spencer reports that although a certain set of steps was generally followed, a woman was “free to utilize the materials at hand for the making of pottery.”[31]

Traditional Additions of Temper to the Clay Bodies

One of the primary challenges of ceramic work is managing the shrinkage and drying of the clay from its wet, plastic state to its dry, brittle state and finally to its fired state. Clay shrinks from 5 to 8 percent from its plastic to dry state, and once vitrified, clay has shrunk up to 10 percent of its plastic volume.[32] The addition of non-plastic particles to the clay can greatly reduce shrinkage. These particles do not absorb as much water as the clay, and their addition facilitates an even drying of the ware by creating an “open” body, essentially pores in the clay through which evaporating water can escape.[33] During firing, water still trapped within the clay can turn to steam and explode the ceramic if it is not given an alternate channel through which to escape. Non-plastic particles such as rock, sand, shell, and crushed previously-fired ceramic are referred to here as “inorganic tempers.” Organic additives to the clay, such as grass, fibers, dung, fats and proteins, are generally meant to alter its modeling properties by making it more plastic and workable or, in the case of fibrous material, by increasing its structural strength in the wet, plastic state.[34] These additives will be referred to here as “organic tempers”.

Inorganic Tempers

Secondary clays, as discussed above, tend to have significant impurities acquired during transport from their source. Often sand or small rocks are mixed into the matrix of a natural clay deposit. It is possible that early practitioners noticed improvements in their ware when using clay with certain kinds of impurities, and began to imitate the more successful natural inclusions by intentional mixing. Sand is the most commonly reported and identified inorganic temper, although crushed rock, shell[35], and other mineral inclusions are found. Potters from the Buckland River area added fine sand to the wet clay. This sand was collected at a location upriver from the clay at a creek called Qiuqtauyaaq, according to Andrew Sunno,[36] suggesting the potters were specific in their choice of temper, presumably with the knowledge that it provided some benefit over other more conveniently available tempers. At St. Michael on Norton Sound, ethnologist Edward William Nelson noted the addition of fine, black, volcanic beach sand to the clay body. [37] At Crow Village, sherds examined by Oswalt were reported to contain sand, gravel and small pebbles.[38] At Hooper Bay an unspecified “crushed rock” was added to the clay along with water, according to Oswalt’s informant.[39] The sherds retrieved by Oswalt support this: most were tempered with crushed rock and small pebbles.[40] Any of these inorganic tempers are acceptable inclusions, and as discussed above, would have helped assist with the drying of the vessel as well as providing structural strength to the fired ware. The choice of temper, the quantity, and the size of the particles all affect the properties of the clay body, as well as the finished vessel’s thermal properties which would be an important consideration in cook ware.[41]

Organic Tempers

As with inorganic tempers, it is likely that the various combinations of location-specific organic tempers were developed by accidental inclusion and trial and error. It is not difficult to imagine a riverbank clay deposit having grass, feathers, and other debris mixed in. An experienced potter is keenly aware of differences between clay bodies, and would immediately recognize the benefit of successful inclusions in the handling of the clay. The combination of both organic and inorganic materials is the most common approach to making a clay body, and the pottery record in Alaska supports this: there are very few cases where organic materials are used alone as tempers.[42] This is not surprising from a technical standpoint: inorganic materials not only reduce plastic shrinkage, and therefore cracking, in the wet clay body, but provide structural support in the dry and fired stages. Organic tempers, however, seem to play an important role in pottery made by hunter-gatherer cultures, where the pottery must, at least occasionally, be transported: organic tempers make for lighter weight ware.[43] In fact, while some hunter-gatherers used both mineral and organic tempers, only non-sedentary cultures used organic tempers exclusively.[44] This suggests that the portability of the vessel may have been prioritized over its strength and durability. In the case of the Alaskan potter, the sheer variety of organic tempers reported in ethnological accounts is evidence that diverse experimentation occurred.

Alec Smart recalled that dog hair and manure were mixed into wet clay at Hooper Bay[45], although the sherds collected there mostly suggested that grass was the main organic additive.[46] It is possible that the small particle size of the dung and hair left very little visible impression in the sherds, where the grass might have left a bolder mark, or perhaps didn’t burn off entirely. In St. Michael, the reported organic temper was “tough blades of a species of marsh grass”.[47] Simon Paneak, in his graphic history of the Nunamiut, included only organic tempers in his recipe for a clay pot: ptarmigan feathers, animal blood, and seal oil. Campbell’s adjacent notes, however, mention that the sherds he examined were tempered with grass,[48] though perhaps this conclusion was reached for the same reasons discussed above. At Crow Village on the Kuskokwim, archaeologists identified grass as the only organic temper in recovered sherds.[49]

Buckland River region tempers described by Andrew Sunno specify that “breast feathers, but no down” were mixed into the clay with the fine sand and water, and all of this was kneaded like dough to the proper consistency on a seal skin which had been laid out for the purpose.[50] On the Yukon, Chief Matthew reported that the clay was mixed with chopped bear’s hair.[51] Again, no hair was seen in the pot sherds examined in the area, rather they appeared to be tempered with fine quartz and schist.[52] This seems to establish a pattern where reported inclusions of certain organic materials are not identified in the analysis of local sherds. However, the claim was backed by Chief Luke of Tanana Mission who also reported to de Laguna that after the clay was dug and stirred, chopped bear hair and sand were added to the paste and then the clay was ready to form.[53] Other sources told of collecting clay from the same location and feathers of seabirds were added (eider and hell-divers were mentioned), with no addition of sand as it was already mixed in with the river clay.[54] At Anvik an informant claimed nose-blood was used in the clay body, and at Nulato a woman described her recipe as flexible to having any kind of oil or fish oil added to it.[55]

At Koyukuk Station, de Laguna was told that some pots were made of a white clay that could be found near a place called Lowden (current maps show only a Louden Slough in Galena, and a New Lowden just west of Galena), and a man from the area claimed that blood was mixed into the clay.”[56] However, Andrew Pilot, also of Koyukuk Station, claimed the clay was mixed with hell-diver feathers and whale or seal oil from Unalakleet or Kotzebue sound,[57] again suggesting the tempers were a matter of personal preference, or perhaps in response to available materials. At Cape Nome in 1877, George Byron Gordon described the mixing of walrus blood into the clay to form a smooth paste to which sand and ptarmigan feathers would be added before modeling.[58]

Anthropologists Drs. Karen Harry and Liam Frink recently refuted claims of blood and oil being mixed into the clay body in any significant quantity, based on problems demonstrated during an attempt to reproduce the traditional techniques of manufacturing a functional arctic cooking pot. In their experiments, the addition of blood to the wet clay body made it more plastic momentarily, but immediately the paste began to harden.[59] They deemed this an impossible working condition, and concluded that reports of blood and oil being mixed into the clay body must be incorrect or misunderstood and that this glue-like quality was likely what made blood an excellent choice for the application as a sealant to the exterior of the pot. But the inclusion of blood in the clay paste is widely reported, and perhaps Frink and Harry misunderstood the desired properties of an arctic clay body. At the very least, it is possible that very small amounts of blood were added to the wet clay body for non-functional purposes. Reflecting on the claim by a man in Anvik that blood from the nose was mixed in, de Laguna writes that, “certainly the amount of blood thus obtained was negligible, but it might have been considered magically potent.”[60] Spencer noted that all of his informants in Barrow agreed that “blood should be free of oil, since the oil prevented congealing.”[61] This suggests the quick hardening of the paste was actually a desired property, and the potters may have worked quickly to form the pot before it hardened.

As evidence that the potters understood the hardening properties of blood, consider the observation of Walter Hough, an ethnologist at the Smithsonian who was studying arctic oil lamps. He wrote, “substitutes for the lamp and cooking pot are sometimes made by Eskimo women from slabs of stone, which they cement together with a combination of seal’s blood, clay, and dog’s hair, applied warm, the vessel being held at the same time over the flame of a lamp, which dries to cement to the hardness of stone.”[62] Clearly the potters understood the properties of their materials, as this combination of ingredients, or something similar, is reported in multiple instances.

Construction Techniques

Accounts of pottery construction techniques are relatively uniform across Alaska, but there is still clear evidence of experimentation with forming methods. At Hooper Bay Alec Smart described the pot bottom as “constructed from one piece of clay, with little pieces pressed onto the bottom to form the sides.”[63] Most of potsherds collected by Oswalt at the Hooper Bay Village site suggest that, in keeping with the majority of pottery found in Alaska, they were constructed with what he refers to as the “patch modeling method.” Just as Smart had recounted, the archeological evidence indicated the vessels began with a large, flat piece of clay for the bottom and the walls were built up by adding small, rectangular patches of clay.[64] The construction technique on the Buckland River was similar, except for one detail. According to Andrew Sunno’s account, the walls were constructed first, “piece by piece”, with bare hands. Once the walls were built up, the clay was shaped and smoothed by hand with one hand inside and one hand outside the vessel, creating opposing forces. Finally, the maker would hold a specialized smoothing tool on the inside, applying pressure against her other hand that was smoothing the outside. This tool was a wooden disc covered with sealskin, hair-side out, with a leather strap on the back under which the maker could slide her hand. Finally, the pot was paddled with a carved wooden rod, imparting both a design, and further compressing the clay.[65] The next step described by Sunno is a departure from other reports of similarly crafted vessels in the arctic and defies a basic rule of pottery construction techniques, whereby clay of similar moisture content must be used when joining pieces together. Due to the high shrinkage of clay as water evaporates from between the particles, joining two pieces of clay at different stages of dryness generally results in cracking apart as the pieces shrink at different rates. The less-dry clay shrinks rapidly as water evaporates off all exposed surfaces, whereas the more-dry clay shrinks slowly as water trapped within the clay slowly penetrates the dry outer surfaces to evaporate.[66] However, Sunno reported that the women in the Buckland River area would not only air dry the walls in the sun, but light a fire inside the walls to further dry them. After cooling, she would make a thick bottom for the pot from the same clay mixture, and attach this wet piece to the dry walls, pressing around the joint. The whole piece was then fired on its side.[67] While it is very surprising that this technique did not cause cracking or separation, it is possible that the clay in use had extremely low plasticity and therefore low shrinkage.

At Koyukuk Station, Andrew Pilot described a method of production that is unique at almost every step, perhaps indicating an unreliable source, or more generously, as de Laguna concluded, described a local method from his hometown of Dolby that, for whatever reason, did not spread beyond that immediate locale. Pilot described the construction of a vessel using a birch bark slump-mold over which the clay was spread and patted down, then left in the sun to dry.[68] De Laguna claimed no evidence of a birch bark mold was ever found, and no one else ever mentioned it. The use of a slump mold would have created a pot with no seams to join, thus reducing the possibility of breakage during drying, firing, and use, along the joints between walls and the bottom, or between the individual patches of clay that made up the walls in the most common forming techniques. Assuming Pilot’s report was accurate, this technique was clearly arrived at by experimentation, and the potter would have surely realized the superiority of a seamless pot. If this method existed, it was a remarkably inventive and clever refinement of pottery construction.

Another unusual account of construction technique comes from ethnologist Edward William Nelson’s report of pottery production in St. Michael on Norton Sound. As in most of the other accounts, the pot bottom is formed from a single piece of clay from which the walls are built up. However, rather than the common patch modeling method, potters at St. Michael built up the walls with “a thin band of clay, carried around a number of times until the desired height is reached.”[69] Nelson is describing the coil-building method, a common hand building technique for the creation of vessels used in prehistoric pottery cultures all over the world. This method is significantly different than the patch-modeling method, suggesting experimentation occurred in the actual construction techniques as well. The coiling method is most suitable to a highly plastic clay that can withstand radial bending, as opposed to the patch modeling method which essentially creates curvature out of flat facets of clay.

Sealing and Firing Techniques

Myriad reasons including the scarcity of fuel, lack of kiln technology, and the high humidity of the arctic summer meant that arctic pottery could not be fired to a temperature sufficient to sinter the ware. Uncarbonized hair and other organic fibers observed in some pot fragments indicate at least some pots were never actually fired, merely fire-hardened. [70] This meant the vessels easily absorbed water and in some cases could disintegrate when wet.[71] Sealing the pot, before or after firing, was critical to making the ware functional.

Along the lower Yukon, pots fragments displayed faint horizontal scratches running around the pot. De Laguna concluded this was evidence of repeated rubbing and smoothing of the exterior which pushed the coarse temper material into the walls and created a smooth clay surface suggesting finer ware.[72] Analysis of the sherds showed that a “false slip” had been achieved by wetting the surface of the clay and further smoothing the pot.[73] While this technique seems to suggest an aesthetic decision, it is likely that the effort actually increased the impermeability of the finished ware. Clay particles are thin hexagonal platelets that can be manipulated by directional compression, such as would be produced by rubbing, to lie flat against each other rather than stacking haphazardly at a variety of angles. This burnishing treatment gives a smooth appearance, but also reduces the porosity of the surface by creating essentially an armor of platelets. Heavily burnished ware was very commonly used in low-fire pottery traditions worldwide, from Sudan to Ireland, before glazes were discovered. In an ethno-archeological study undertaken in Kathmandu Valley, for example, traditional potters explained the desirability of burnishing their pots: “it makes them less porous so that they do not soak up all the wine”.[74] Adding water to the surface of a clay pot and smoothing with a stone is still one of the most common burnishing practices used in modern ceramics today.[75] While there are no known reports of “burnished” pottery in arctic Alaska, the use of the false slip and smoothing of the surface indicate the method could have been in use. Perhaps the lack of evidence for true burnishing in the archaeological record is due to the friability of the low-fired ware, and its tendency to slough and flake over time, whereby the surface layer would be the first to break down.

The primary sealant reported for vessels was seal oil, although the application method and timing vary widely. In Hooper Bay, seal oil was applied to the pot only after a preliminary firing, and then the pot was re-fired.[76] Of the Buckland River technique, Sunno describes a two-part firing process: initially the walls alone were air-dried and a fire was lit between them for further drying. A wet bottom was attached and the whole pot was turned on its side. A hot wood fire was built around it, hot enough to turn the ware red. The pot was occasionally turned so each side would be evenly fired, and then oiled while still warm from the fire. Seal oil was applied both inside and out, and the pot was ready for use.[77]

Frank Andrew of Kwigillingok described the firing of a clay lamp to Ann Fienup-Riordan in a 2003 interview. He explained that the lamp was covered in grass and allowed to air dry, before being coated in oil, placed in the fire and “burnt.”[78] At Hooper Bay, the pot would be allowed to dry in the air for a “short while,” according to Oswalt’s source, and then placed in a hot fire. After it was fired “sufficiently”, it was removed, cooled, smothered in seal oil, and returned to the fire for an additional firing. If the pot held water the process was complete.[79] At Nulato, a woman described leaving the finished pot to dry by the fire all day, where it was frequently greased and turned around. Any kind of oil could be used to grease the pot both during its fire-side firing, and then again after each use for cooking. [80]

At St. Michael on Norton sound, Nelson reported that the vessel was placed near the fire until dry, and then a fire was lit both inside and around it and fired for “an hour or two with as great heat as can be obtained.”[81] This description differs from most other methods reported not just because of the interior fire, but because it implies very active tending and control of the fire in order to keep temperatures high. As with the previous steps of pottery production, the sealing and firing processes reported at different locations in Alaska indicate either individual preferences or the development of techniques suitable to the environment and resources at hand.

Tools Associated with Pottery Production

Many examples of arctic Alaskan pottery exhibit surface decorations and textures, the significance of which is a topic too broad to cover here, and is not an example of the technology of pottery production. The tools used to make the pots, and in many cases make the decorative marks, should be addressed here, since they represent technology developed in support of the manufacture of ceramic ware. Some of the reported tools assisted with the construction of the pots, and some were for decorative purposes only. At Hooper Bay, shells, bones and pieces of wood were used for impressing precise designs into the wet clay, and Oswalt suggests grass mats were used as a vessel-building platform, leaving a distinct impression on the bottom of the pots. [82] At Buckland River Andrew Sunno reported that ugruk was laid out for wedging clay and fillers, and a sealskin covered wooden disk with a leather hand strap was used as a smoothing tool. A wooden paddle was used for compressing the walls of the pot, and was carved to simultaneously impart a dentition pattern.[83] On the lower Yukon, small round stones with the lower edge ground smooth were found at Anvik Point and Bonasila, and identified as pottery smoothers by local sources. De Laguna suggests they are scrapers. [84] Indeed, the shape sounds similar to what is commonly called a “rib” in the toolset of the modern potter, and consists of a flat rubber, metal or wood oblong semi-circle used to scrape, compress and smooth the inner walls of a pot with its convex edge. It is not surprising that such a tool would be used to help further join and blend the multiple seams created by the patch modeling method commonly employed.

Storage and Handling

Great care had to be taken with these low-fired pots to prevent breakage and the absorption of moisture. Because many of the pots were constructed by the patch modeling method they would fracture along the patch seams, and pot sherds recovered from archaeological sites were often nearly rectangular or triangular as were the patches. [85] Andrew Pilot of Koyukuk Station told de Laguna that the local pots were easily broken, and so were always carried in cases of skin.[86] Along the lower Yukon (Shageluk, Anvik, Holy Cross) Osgood reports that pots were packed with grass in a birch bark basket for transport.[87] Andrew Sunno reported that the Buckland woman cared for her pot by immediately bailing water out of the pot after cooking and would set it upside down to drain, away from the fire.[88] Although Lucier supposed the Buckland pots were wrapped in haired skins or grass mats for fall and winter transport, there was no account of the actual method used.[89] When a pot did break, there was often an attempt to mend it. In Barrow, Spencer observed that a broken pot would be repaired with a paste of additional clay, feathers, and blood and then refired. [90] At other sites, sherds from broken pots were discovered with holes drilled along the fissure so the pieces could be lashed back together. This technique was observed at Crow Village to the surprise of the archaeologists who found European ware mended with this technique. Oswalt and VanStone described the find: “A single sherd has a drilled hole near one edge, indicating an attempt to repair a broken vessel by a method commonly used with traditional Eskimo pottery.” [91]

Summary

Ethnographic reports collected in the twentieth century depict a ceramic tradition that highlights an oft-repeated praise of the indigenous people of the Alaskan arctic: their possession of technical ingenuity and the ability to address the challenges of their environment in extraordinary ways. The widespread use of pottery and the distinct variations in material and technique between various localities reaffirms this due praise. The traditional ceramic technology of Alaska reflects the creativity, flexibility and experimental attitude with which the indigenous people met their needs in an often harsh, and always challenging, arctic environment.

Notes:

[2] David Adams Leeming and Margaret Adams Leeming, Encyclopedia of Creation Myths,Vol. 1, (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1994), 133.

[3] Wu XiZhang, Goldberg P, Cohen D, Pan Y, Arpin T, and Bar-Yosef O, 2012. “Early pottery at 20,000 years ago in Xianrendong Cave, China,” Science 336, 1696-1700.

[4] Shelby L. Anderson, Matthew T. Boulanger, and Michael D. Glascock, “A New Perspective on Late Holocene Social Interaction in Northwest Alaska: Results of a Preliminary Ceramic Sourcing Study,” Journal of Archaeological Science 38, no. 5 (2011), 945.

[5] Shelby L.R. Anderson, From Tundra to Forest: Ceramic Distribution and Social Interaction in Northwest Alaska, thesis, University of Washington, 2011, 24.

[6] Shelby L. Anderson, Matthew T. Boulanger, and Michael D. Glascock, “A New Perspective on Late Holocene Social Interaction in Northwest Alaska: Results of a Preliminary Ceramic Sourcing Study,” Journal of Archaeological Science 38, no. 5 (2011), 945.

[7] Shelby L.R. Anderson, From Tundra to Forest: Ceramic Distribution and Social Interaction in Northwest Alaska, thesis, University of Washington, 2011, 27.

[8] Don E. Dumond, “The Archaeology of Migrations: Following the Fainter Footprints.” Arctic Anthropology 2 (1998), 59.

[9] L. M. Frink, “The Social Role of Technology in Coastal Alaska,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13, no. 3 (2009), 295.

[10] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[11] L. M. Frink, “The Social Role of Technology in Coastal Alaska,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13, no. 3 (2009), 295.

[12] Wendell H. Oswalt, and James W. VanStone. The ethnoarcheology of Crow Village, Alaska. No. 199. (US Govt. Print. Off., 1967), 74.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ann Fienup-Riordan, The Way We Genuinely Live = Yuungnaqpiallerput : Masterworks of Yup’ik Science and Survival, (Seattle: University of Washington, 2007), 292.

[15] Vilhjálmur Stefánsson, The Stefánsson-Anderson Arctic Expedition of the American Museum Preliminary Ethnological Report (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1914), 312.

[16] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[17] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18:1 (July 1952), 18.

[18] John Martin Campbell, North Alaska Chronicle: Notes from the End of Time : The Simon Paneak Drawings (Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1998), 1.

[19] Ibid, 2.

[20] Ibid, Plate 40.

[21] Ann Fienup-Riordan, The Way We Genuinely Live = Yuungnaqpiallerput : Masterworks of Yup’ik Science and Survival, (Seattle: University of Washington, 2007), 4.

[22] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[23] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18:1 (July 1952), 18.

[24] Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian, Being a Series of Volumes Picturing and Describing the Indians of the United States and Alaska., vol. 20 (Seattle: E.S. Curtis, 1930), 97-98.

[25] Ibid, 51.

[26] Robert F. Spencer, “The North Alaskan Eskimo: A Study in Ecology and Society”. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 171 (1959), 471.

[27] Frederica De Laguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 140.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Edward William Nelson, “The Eskimo About Bering Strait. Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report 18: 19-518.” Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1899), 201.

[30] Daniel Rhodes, Clay and Glazes for the Potter. (New York: Greenberg, 1957), 37.

[31] Robert F. Spencer, “The North Alaskan Eskimo: A Study in Ecology and Society”. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 171 (1959), 472.

[32] Daniel Rhodes, Clay and Glazes for the Potter. (New York: Greenberg, 1957), 12-13.

[33] Ibid, 13.

[34] James M. Skibo, Michael B. Shiffer, and Kenneth C. Reid, “Organic-Tempered Pottery: An Experimental Study,” American Antiquity 54, no. 1 (January 1989),135-136.

[35] In a 1939 personal correspondence to de Laguna, Dr. Robert F Heizer describes potsherds he encountered at Alitak Bay on Kodiak Island as “thick, black, shell tempered, crumbly pottery.” De Laguna reports that she is unaware of another instance of shell used as temper in “Eskimo” pottery. Frederica De Laguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 245.

[36] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[37] Edward William Nelson, “The Eskimo About Bering Strait. Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report 18: 19-518.” Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1899), 201.

[38] Wendell H. Oswalt and James W. VanStone. (The ethnoarcheology of Crow Village, Alaska. No. 199. US Govt. Print. Off. 1967), 46.

[39] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18, no.1(July 1952), 18.

[40] Ibid, 26.

[41] Shelby L.R. Anderson, From Tundra to Forest: Ceramic Distribution and Social Interaction in Northwest Alaska, thesis, University of Washington, 2011, 99.

[42] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18, no. 1 (July 1952), 27.

[43] James M. Skibo, Michael B. Shiffer, and Kenneth C. Reid, “Organic-Tempered Pottery: An Experimental Study,” American Antiquity 54, no. 1 (January 1989), 123.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18, no. 1 (July 1952), 18.

[46] Ibid, 26.

[47] Frederica deLaguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 228.

[48] John Martin Campbell, North Alaska Chronicle: Notes from the End of Time : The Simon Paneak Drawings (Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1998), Plate 40.

[49] Wendell H. Oswalt and James W. VanStone, The ethnoarcheology of Crow Village, Alaska. No. 199. (US Govt. Print. Off. 1967), 46.

[50] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[51] Frederica deLaguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 141.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Frederica deLaguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 141.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid.

[58] George Byron Gordon, Notes on the western Eskimo, (University of Pennsylvania, Department of Archaeology, 1906), 74.

[59] Karen G. Harry, Lisa Frink, Brendan O’Toole, and Andreas Charest. “How to Make an Unfired Clay Cooking Pot: Understanding the Technological Choices Made by Arctic Potters.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 16.1 (2009), 40-41.

[60] Frederica de Laguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 141.

[61] Robert F. Spencer, “The North Alaskan Eskimo: A Study in Ecology and Society”. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 171 (1959), 472.

[62] Walter Hough, The Lamp of the Eskimo. (Washington: Govt. Print. Off., 1898), 1032.

[63] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18, no. 1 (July 1952), 18.

[64] Ibid, 26.

[65] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[66] Susan Peterson and Jan Peterson, The Craft and Art of Clay: A Complete Potter’s Handbook (London: Laurence King, 2003), 23.

[67] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[68] Frederica de Laguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 141.

[69]Edward William Nelson, “The Eskimo About Bering Strait. Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report18: 19-518,” Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1899), 201.

[70] Karen G. Harry et al., “How to Make an Unfired Clay Cooking Pot: Understanding the Technological Choices Made by Arctic Potters,” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 16, no. 1 (2009), 38.

[71] Ibid, 39.

[72] Frederica deLaguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 143.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Judy Birmingham, “Traditional Potters of the Kathmandu Valley: An Ethnoarchaeological Study,” Man, New Series, 10, no. 3 (September 1975), 378.

[75] Sumi VonDassow, “Going Low Tech: A Step by Step Guide to Burnishing Pottery,” Ceramic Arts Daily RSS, April 25, 2011, http://ceramicartsdaily.org/pottery-making-techniques/ceramic-decorating-techniques/going-low-tech-a-step-by-step-guide-to-burnishing-pottery/.

[76] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18, no. 1 (July 1952), 18.

[77] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[78] Ann Fienup-Riordan, The Way We Genuinely Live = Yuungnaqpiallerput : Masterworks of Yup’ik Science and Survival, (Seattle: University of Washington, 2007), 292.

[79] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18, no. 1 (July 1952), 18.

[80] Frederica deLaguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 141.

[81] Edward William Nelson, “The Eskimo About Bering Strait. Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report18: 19-518,” Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1899), 201.

[82] Wendell Oswalt, “Pottery from Hooper Bay Village, Alaska,” American Antiquity 18, no. 1 (July 1952): 18.

[83] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[84] Frederica deLaguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 142.

[85] Frederica deLaguna, The Prehistory of Northern North America as Seen from the Yukon, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology vol. 3, (Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology, 1947), 143.

[86] Ibid, 141.

[87] Osgood, 1940, pp. 146-149.

[88] Charles V. Lucier and James W. VanStone, “Historic Pottery of the Kotzebue Sound Iñupiat”, Fieldiana: Anthropology, New Series, No.18 (Chicago, IL: Field Museum of National History, 1992), 4.

[89] Ibid, 5.

[90] Robert F. Spencer, “The North Alaskan Eskimo: A Study in Ecology and Society”. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 171 (1959): 472.

[91] Wendell H. Oswalt, and James W. VanStone. The ethnoarcheology of Crow Village, Alaska. No. 199. (US Govt. Print. Off., 1967), 53.

[1]Osgood, Cornelius. 1940. Ingalik material culture [by] Cornelius Osgood. n.p.: New Haven, Pub. for the Department of anthropology, Yale university, by The Yale university press; London, H. Milford, Oxford university press, 1940.